A deeply reported AP investigation exposed the human rights and environmental impact of mining for the rare earth metals vital to high tech.

Extensive reporting by an Associated Press investigative team found that the mining of rare earth elements in Myanmar hides a dirty open secret: Their cost is environmental destruction, the theft of land from villagers and the funneling of money to brutal militias, including at least one linked to Myanmar’s secretive military government.

Rare earth metals reach into the lives of almost everyone on the planet, turning up in everything from hard drives and cellphones to elevators and trains. They are especially vital to the fast-growing field of green energy, used in wind turbines and electric car engines. In a cruel twist, as demand soars for clean energy, the abuses are likely to grow.

Reporters Victoria Milko in Jakarta, Indonesia, and Lori Hinnant, based in Paris, had each noticed opaque references to China’s rare earth supply chain and wanted to know what was behind it.

They teamed up with Asia-based investigative reporter and video journalist Dake Kang to dig deeper, using his expertise on that county’s supply chains, finding links to Europe and North America. Meanwhile, AP researcher Si Chen in China spoke to miners who had labored in Myanmar; they described a web of small, primitive, unlicensed mines that sell to China’s big state-owned mining conglomerates.

The reporters worked with digital illustrator Peter Hamlin and video journalist Shelby Lum in New York and digital storyteller Dario Lopez in Phoenix to create “The Sacrifice Zone” an immersive package revealing how demand for rare earths incentivizes destructive practices, and how the metals are found in the supply chains of some of the most prominent companies in the world, including General Motors, Volkswagen, Mercedes, Tesla and Apple.

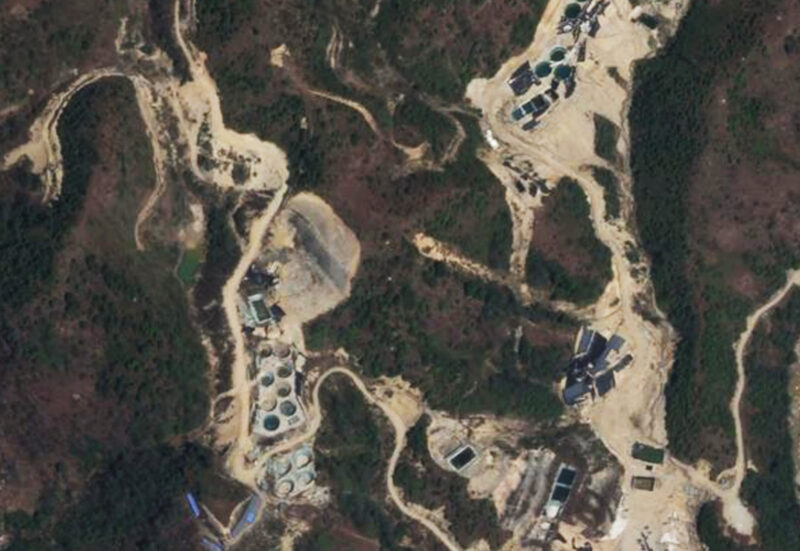

The multiformat AP investigation drew on dozens of interviews, customs data, corporate records and Chinese academic papers, along with satellite imagery and geological analysis by environmental nonprofit Global Witness, tying rare earths from Myanmar to the supply chains of 78 companies.

About a third of the companies responded to AP’s queries. Of those, about two-thirds didn’t or wouldn’t comment on their sourcing, including Volkswagen, which said it was conducting due diligence for rare earths. GM said it understood “the risks of heavy rare earths metals” and would source from an American supplier soon. Nearly all said they took environmental protection and human rights seriously.

Mary Rajkumar, deputy editor for international investigations, handled the text edit; Jeannie Ohm, Washington news editor for video, produced the video piece; and Raghu Vadarevu, digital editor for global investigations, developed the online presentation.

While other news organizations have covered the rare earths supply chain, none have had the depth and range of AP’s reporting. The AP story was widely cited by human rights groups and international governmental agencies. The U.S. State Department said after the story ran that it was “deeply concerned” about illicit mining operations in Myanmar. But no less rewarding, the editor of a small-town newspaper in central Pennsylvania wrote AP: “It makes me feel like I chose the right profession when I see stories like this. ... Thank you so much for giving journalism a good name.”

For this global exclusive about the complex, disturbing intersection of green supply chains and human rights abuses, the team of Kang, Milko, Hinnant, Chen, Lum, Hamlin and Lopez is AP’s Best of the Week — Second Winner.

Visit AP.org to request a trial subscription to AP's video, photo and text services.

For breaking news, visit apnews.com.